|

Download a PDF of this report:

|

| ||

|

Waterloo Region is no stranger to name changes and fluid political boundaries. Berlin became Kitchener after a referendum in 1916. Cambridge was created out of the towns of Galt, Preston, and Hespeler in 1973. Waterloo was a village in 1857, a town in 1876, and a city in 1948. Since 1973, Waterloo Region has been a two-tier municipality consisting of 3 cities (Cambridge, Kitchener, and Waterloo) and 4 townships (North Dumfries, Wellesley, Wilmot, and Woolwich).

Despite this familiarity with changing municipal structures, Amalgamation has been a contentious topic in the region. In the 1990s, the provincial government of Mike Harris initiated a wave of municipal amalgamations and Waterloo Region very nearly became one of them. Referendum questions about amalgamation in 2011 were met with strong opposition (in Waterloo) and strong support (in Kitchener).

In 2019, the provincial government of Doug Ford commissioned Ken Seiling and Michael Fenn to report on municipal government reform, but their report was never made public. In fall 2022 the same provincial government passed legislation focussed on reform and with Waterloo Region as one of the regions to be considered. |

Held June 1st, 2023: |

In this context, Waterloo Regional Councillor Rob Deutschmann gathered a panel of speakers to reflect on whether amalgamation is the future of governance in Waterloo Region. Their perspectives ranged from historical, to supportive, to opposed. They considered academic research on amalgamation, questions of civic identity, and the state of competition amongst the regions of Ontario.

Speakers included:

Ken Seiling

Ken was a Councillor and Mayor in Woolwich township, and then chair of Waterloo Region from 1985 until 2018. Ken set the stage for later speakers by reviewing the history of Waterloo Region and Waterloo County before that. Waterloo County was created in 1853, followed quickly by the establishment of a courthouse. Over the course of the twentieth century, boundary changes were considered. In the 1970s, Waterloo Region as we currently know it came into being. Since then, there has been a steady but muted conversation about how the people of the region might be better served by different municipal structures. Formal reviews and informal discussion has led to little substantive reform.

Despite advice in the early 1990s that the two-tier water and sewer systems ought to be merged, nothing ever became of the effort. In the late 1990s, discussions of region-wide amalgamation took place. Although many parts of Ontario such as Toronto, Ottawa, and Hamilton, were amalgamated, Waterloo Region did not make the list of reformed regions. Since then there has been little appetite to discuss it locally. Instead, cooperation between municipalities has led to some amalgamation of services. The 2022 merger of Kitchener-Wilmot Hydro Inc and Waterloo-North Hydro Inc to form Enova Energy Corporation is a fresh example. In general, discussions of municipal restructuring and reform have been characterised by “glacial inaction”.

Cost savings from regional reforms are very difficult to quantify, as they took place in the context of service realignments that added more responsibility to local governments.

At the behest of Ontario Premier Doug Ford, Ken carried out an engagement and analysis report regarding regional reform with Michael Fenn. Although the report was completed and submitted to the province, the work is covered by a non-disclosure agreement, and we weren’t able to hear any details. Ken did say that it was (and remains) “...thoroughly researched and well documented, and carried recommendations which would have seen, in my opinion, a much more robust municipal system than we currently have in place across much of Ontario.” With the recent passing of BIll 59 in Ontario, we may well revisit this work as a facilitator is named to review the Region of Waterloo.

Takeaways:

Despite advice in the early 1990s that the two-tier water and sewer systems ought to be merged, nothing ever became of the effort. In the late 1990s, discussions of region-wide amalgamation took place. Although many parts of Ontario such as Toronto, Ottawa, and Hamilton, were amalgamated, Waterloo Region did not make the list of reformed regions. Since then there has been little appetite to discuss it locally. Instead, cooperation between municipalities has led to some amalgamation of services. The 2022 merger of Kitchener-Wilmot Hydro Inc and Waterloo-North Hydro Inc to form Enova Energy Corporation is a fresh example. In general, discussions of municipal restructuring and reform have been characterised by “glacial inaction”.

Cost savings from regional reforms are very difficult to quantify, as they took place in the context of service realignments that added more responsibility to local governments.

At the behest of Ontario Premier Doug Ford, Ken carried out an engagement and analysis report regarding regional reform with Michael Fenn. Although the report was completed and submitted to the province, the work is covered by a non-disclosure agreement, and we weren’t able to hear any details. Ken did say that it was (and remains) “...thoroughly researched and well documented, and carried recommendations which would have seen, in my opinion, a much more robust municipal system than we currently have in place across much of Ontario.” With the recent passing of BIll 59 in Ontario, we may well revisit this work as a facilitator is named to review the Region of Waterloo.

Takeaways:

- Reform has not emerged organically except in narrow areas such as garbage collection and transit.

- Reform is most often considered under the possibility of provincial intervention.

- Regional reform is more important than ever. The status quo is not a recipe for the future health of the Region.

Zac Spicer

Zac is an Associate Professor in the School of Public Policy and Administration at York University, with a research focus in municipal governance. He has lived in both Waterloo Region and the city of Hamilton.

Zac contrasted Waterloo Region with his current location in Hamilton, to illustrate the strengths and weaknesses of the two different structures. The current city of Hamilton was created in 2001 following an amalgamation. It encompasses both the “steel city” but also vast agricultural areas in an area of 1200 square kilometres. The size of the city and diversity of environment makes it difficult to reconcile different needs within a single municipality. One can find residents that believe the city is controlled by the suburbs, while some believe exactly the opposite. Simmering resentments and distrust amongst the different parts of the city loom over many discussions. The city is of a size that is too big to respond to some local issues while being too small to have a meaningful impact on provincial policy. An ongoing debate about “area ratings” sets different taxation levels to match different service delivery realities (such as transit in the rural parts of Hamilton). This type of conflict has also been seen in the amalgamated City of Ottawa, and even with the current Region of Waterloo.

The costs associated with an amalgamation tend to be high, including the challenges in harmonising services across formerly independent areas. There has been no clear cost savings. There is even a concern that the amalgamation has given rise to a risk of increased costs due to a reduction in competition. There is a reduced set of options presented to prospective residents of Hamilton, who would have had a choice in municipality prior to amalgamation.

The redistributive role of a large municipality allows resources to be redirected from wealthy areas to less affluent ones, which leads to an argument that Hamilton has become a more equitable city than it was prior to amalgamation. The example of Hamilton offers caution and promise to the Region of Waterloo, but Zac warns that it is very difficult to de-amalgamate. Other speakers will also speak to the challenges in unwinding a single municipality into multiple smaller (yet still single-tier) municipalities.

Takeaways:

Zac contrasted Waterloo Region with his current location in Hamilton, to illustrate the strengths and weaknesses of the two different structures. The current city of Hamilton was created in 2001 following an amalgamation. It encompasses both the “steel city” but also vast agricultural areas in an area of 1200 square kilometres. The size of the city and diversity of environment makes it difficult to reconcile different needs within a single municipality. One can find residents that believe the city is controlled by the suburbs, while some believe exactly the opposite. Simmering resentments and distrust amongst the different parts of the city loom over many discussions. The city is of a size that is too big to respond to some local issues while being too small to have a meaningful impact on provincial policy. An ongoing debate about “area ratings” sets different taxation levels to match different service delivery realities (such as transit in the rural parts of Hamilton). This type of conflict has also been seen in the amalgamated City of Ottawa, and even with the current Region of Waterloo.

The costs associated with an amalgamation tend to be high, including the challenges in harmonising services across formerly independent areas. There has been no clear cost savings. There is even a concern that the amalgamation has given rise to a risk of increased costs due to a reduction in competition. There is a reduced set of options presented to prospective residents of Hamilton, who would have had a choice in municipality prior to amalgamation.

The redistributive role of a large municipality allows resources to be redirected from wealthy areas to less affluent ones, which leads to an argument that Hamilton has become a more equitable city than it was prior to amalgamation. The example of Hamilton offers caution and promise to the Region of Waterloo, but Zac warns that it is very difficult to de-amalgamate. Other speakers will also speak to the challenges in unwinding a single municipality into multiple smaller (yet still single-tier) municipalities.

Takeaways:

- Hamilton is the result of an amalgamation of urban and rural areas in 2001, with ongoing conflicts between those areas.

- It is difficult to quantify any financial benefits of amalgamation.

- De-amalgamation, the process of separating parts of a single-tier region, is very difficult and should lead to caution in amalgamation processes.

Phil Marfisi

Q: What did the regional government say to the lower level municipality that was upset about amalgamation hot happening?

A: This isn’t worth shedding any tiers over!

Phil is the Governance Coordinator at Wilfrid Laurier University and a fan of community engagement but he participated in the panel as a concerned and engaged citizen. Phil began by emphasising the importance of engaging with the public and considering formal research, speaking to the recent conversation in Waterloo Region and global experiences.

It’s important to realize that democracy involves both elected leaders and unelected or informal participants with lived experience of the Region of Waterloo. In a civic conversation as important, with consequences that will be felt for generations to come, that engagement with both elected and informal members of the community as well as to incorporate formal research and best practices.

Some recent themes, right or wrong, that have been part of the conversation on amalgamation have included:

A challenge with this local framing is that it assumes good intentions, may not reference experiences in other jurisdictions, and doesn’t acknowledge research that addresses these concerns and questions.

Antonio Tavares of the University of Minho studied amalgamations and concluded that economies of scale are unlikely, and that expected cost-savings tend to disappear. For better or for worse, larger bureaucracies are more expensive to run. Nevertheless, improved service delivery is possible. Connecting back to a previous town hall, mergers also tend to depress election turnouts. Tavares’ research drew on experience from 52 jurisdictions around the world, including ten in Canada with some in Ontario. On the theme of local democracy, his research concluded that “...mergers tend to depress turnout rates, reduce internal political efficacy (1), and negatively affect the level of community attachment of residents. The findings in this category are quite robust across countries and research…” Tavares concluded that amalgamation is not the only strategy for addressing concerns around local goveranance.

Research at the University of Guelph focussed on Ontario amalgamations in Ontario during the 1990s and found that savings were “marginal at best” with a clear reduction of representation on new councils in many cases. Drs Slack and Bird, faculty at the University of Toronto found pros and cons that make it draw mixed conclusions about the benefits of amalgamations. In favour is a simplification of structures that make it easier for residents to understand their governance, the potential for better fiscal accountability, and a larger tax base that may lead to more equitable service delivery. But these advantages are balanced by reduced access, a less responsive and increasingly bureaucratic service organization, and elusive or unrealized economies of scale. Two-tier structures also come with advantages and disadvantages. The research does not give a clear “winner”.

It is valuable to ask “Is amalgamation a solution in search of a problem?”

Takeaways:

(1) “Political efficacy” refers to citizens’s sense of agency in feeling like they can influence political affairs

A: This isn’t worth shedding any tiers over!

Phil is the Governance Coordinator at Wilfrid Laurier University and a fan of community engagement but he participated in the panel as a concerned and engaged citizen. Phil began by emphasising the importance of engaging with the public and considering formal research, speaking to the recent conversation in Waterloo Region and global experiences.

It’s important to realize that democracy involves both elected leaders and unelected or informal participants with lived experience of the Region of Waterloo. In a civic conversation as important, with consequences that will be felt for generations to come, that engagement with both elected and informal members of the community as well as to incorporate formal research and best practices.

Some recent themes, right or wrong, that have been part of the conversation on amalgamation have included:

- The current structure involving townships, cities, and the Region “doesn’t make sense” and creates obstacles to progress. Confusion coming from complicated two-tier structures emerges as a real problem in situations such as the attraction of investment, or in managing a public health crisis such as the pandemic. Difficulties in attracting investment limits economic development.

- Combining municipalities would lead to cost savings, fewer politicians, and more efficiencies.

- A sense that “bigger is better”.

- Finally, a sense that if there is not local movement towards amalgamation, that the province will step in and “do it for us”.

A challenge with this local framing is that it assumes good intentions, may not reference experiences in other jurisdictions, and doesn’t acknowledge research that addresses these concerns and questions.

Antonio Tavares of the University of Minho studied amalgamations and concluded that economies of scale are unlikely, and that expected cost-savings tend to disappear. For better or for worse, larger bureaucracies are more expensive to run. Nevertheless, improved service delivery is possible. Connecting back to a previous town hall, mergers also tend to depress election turnouts. Tavares’ research drew on experience from 52 jurisdictions around the world, including ten in Canada with some in Ontario. On the theme of local democracy, his research concluded that “...mergers tend to depress turnout rates, reduce internal political efficacy (1), and negatively affect the level of community attachment of residents. The findings in this category are quite robust across countries and research…” Tavares concluded that amalgamation is not the only strategy for addressing concerns around local goveranance.

Research at the University of Guelph focussed on Ontario amalgamations in Ontario during the 1990s and found that savings were “marginal at best” with a clear reduction of representation on new councils in many cases. Drs Slack and Bird, faculty at the University of Toronto found pros and cons that make it draw mixed conclusions about the benefits of amalgamations. In favour is a simplification of structures that make it easier for residents to understand their governance, the potential for better fiscal accountability, and a larger tax base that may lead to more equitable service delivery. But these advantages are balanced by reduced access, a less responsive and increasingly bureaucratic service organization, and elusive or unrealized economies of scale. Two-tier structures also come with advantages and disadvantages. The research does not give a clear “winner”.

It is valuable to ask “Is amalgamation a solution in search of a problem?”

Takeaways:

- Amalgamation is not a silver bullet for the challenges facing municipalities

- Financial benefits are at best, mixed.

- Mergers can have negative effects on democratic engagement

(1) “Political efficacy” refers to citizens’s sense of agency in feeling like they can influence political affairs

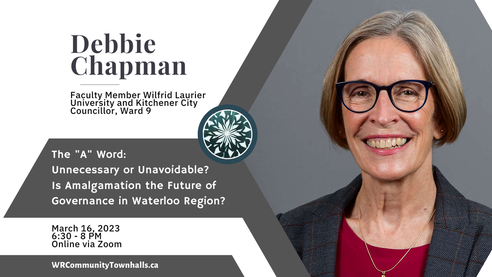

Debbie Chapman

Debbie is a faculty member at Wilfrid Laurier University and the councillor for Ward 9 on Kitchener City Council. She strongly advocated that any major reform to municipal structures ought to go through a community engagement and referendum process. This is in stark contrast to recent experience in Ontario, where reform is imposed downward by the provincial government. Debbie also distinguishes between amalgamation of councils and amalgamation of services.

2011 referenda in Kitchener and Waterloo had radically different results, with Kitchener residents strongly supporting a dialogue on amalgamation and Waterloo residents strongly opposed. Consultation is required to understand and overcome this gulf if there is to be an amalgamation discussion that is centred on the people that live in Waterloo Region.

With fewer elected leaders in an amalgamated Region, those leaders would be further away from the people that they are to represent. That’s to say that if each elected leader is representing a larger constituency, there will be less “leader” to go around. One could also imagine that the way in which resources are allocated would also change.

Amalgamation of services is a different type of conversation, where an a la carte approach could focus on areas where benefits can be achieved while avoiding areas where it is much less likely. Considering Kitchener and Waterloo, the two cities are already engaged in many joint strategies, and these are listed on a website:

Considering immediate and specific projects and services, the following are a few of the collaborations between the cities:

2 www.kitchener.ca/en/council-and-city-administration/joint-services-with-waterloo.aspx

Services and work can always be amalgamated without wholesale structural change in the region. This can be done quickly and tactically, as the need arises.

Debbie highlighted the uncertainty around Bill 39, The Better Municipal Governance Act, and the facilitation of municipal reform that it prescribes along with the strong mayoral powers granted to Ottawa and Toronto in Bill 39. She related research into de-amalgamation in the Montreal and Winnipeg areas, and the political challenges around making it happen as well as the costs. The research was undertaken by Zac Spicer (the very same one that spoke earlier on this panel) and his colleague Lydia Miljan, and the report can be found on the website of the Fraser Institute. The resarch found that amalgamation cannot be assumed to produce cost savings, and separates residents from their leadership. Nevertheless, de-amalgamation offers no assurance of lowered costs or improved services.

A few questions to consider in any discussion of structural amalgamation…

Takeaways:

2011 referenda in Kitchener and Waterloo had radically different results, with Kitchener residents strongly supporting a dialogue on amalgamation and Waterloo residents strongly opposed. Consultation is required to understand and overcome this gulf if there is to be an amalgamation discussion that is centred on the people that live in Waterloo Region.

With fewer elected leaders in an amalgamated Region, those leaders would be further away from the people that they are to represent. That’s to say that if each elected leader is representing a larger constituency, there will be less “leader” to go around. One could also imagine that the way in which resources are allocated would also change.

Amalgamation of services is a different type of conversation, where an a la carte approach could focus on areas where benefits can be achieved while avoiding areas where it is much less likely. Considering Kitchener and Waterloo, the two cities are already engaged in many joint strategies, and these are listed on a website:

- Vision Zero approach to traffic safety

- A plan for inclusionary zoning

- An affordable housing strategy

Considering immediate and specific projects and services, the following are a few of the collaborations between the cities:

- The maintenance of twenty border streets, including snow removal and general upkeep

- Joint fire dispatch to Kitchener, Waterloo, and Cambridge

- Advocacy for two-way all-day GOTrain Service between the Region and GTA

- The Waterloo Regional Small Business Centre

2 www.kitchener.ca/en/council-and-city-administration/joint-services-with-waterloo.aspx

Services and work can always be amalgamated without wholesale structural change in the region. This can be done quickly and tactically, as the need arises.

Debbie highlighted the uncertainty around Bill 39, The Better Municipal Governance Act, and the facilitation of municipal reform that it prescribes along with the strong mayoral powers granted to Ottawa and Toronto in Bill 39. She related research into de-amalgamation in the Montreal and Winnipeg areas, and the political challenges around making it happen as well as the costs. The research was undertaken by Zac Spicer (the very same one that spoke earlier on this panel) and his colleague Lydia Miljan, and the report can be found on the website of the Fraser Institute. The resarch found that amalgamation cannot be assumed to produce cost savings, and separates residents from their leadership. Nevertheless, de-amalgamation offers no assurance of lowered costs or improved services.

A few questions to consider in any discussion of structural amalgamation…

- Would amalgamation address the affordable housing crisis?

- Would amalgamation address homelessness?

- Would amalgamation make for a more equitable society?

- Would amalgamation serve to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and address the climate emergency?

- How would amalgamation impact the democratic process?

- Who benefits from amalgamation?

Takeaways:

- Decisions must be taken locally, and not imposed from above

- Amalgamation of councils will further separate them from the people

- Amalgamation of services is already very common

Doug Craig

Doug is a Waterloo Region councillor and Former Mayor of Cambridge (which also placed him on Waterloo Region Council). Cambridge was formed from an amalgamation of the towns of Galt, Preston, Hespeler, and their surrounding areas in the early 1970s. Doug has experienced the effects first-hand as a leader in that city.

He recounted the experience in Toronto, where fiscal savings never materialized. Despite promises of $300,000,000 savings, this was steadily walked back and has never. Amalgamation draws attention away from the other crises that we face - homelessness, and substance abuse. It distracts from these real problems.

Doug observes that municipal governments are among the best-run in the country, with balanced budgets, excellent transparency, and good connections to the people that they represent and serve. Particularly concerning is the regular interventions by the provincial government in municipal affairs, creating worrying uncertainty about the direction we’re being taken. Doug mentions that this distraction caused by provincial interference has been ongoing for twenty years. He asks some questions…

By many measures, Waterloo Region has been very successful with its current structure, leading one to wonder what the proposed benefit would be. Comparisons to the United States, London (UK), and Paris (France) show that unamalgamated cities with multiple tiers are common and successful. In the USA (San Francisco and Boston as examples that also have strong technology sectors), a dearth of amalgamations in the last century has led to many municipalities working well together in close proximity. Cooperation agreements are the normal way of working together rather than the consolidation of political structures. There are many global cities that have succeeded with reducing to a single-tier structure.

Doug challenges “Why would you want to amalgamate the Region of Waterloo?”, because based on many measures there is little room to improve on the performance of an already topnotch region.

Takeaways:

He recounted the experience in Toronto, where fiscal savings never materialized. Despite promises of $300,000,000 savings, this was steadily walked back and has never. Amalgamation draws attention away from the other crises that we face - homelessness, and substance abuse. It distracts from these real problems.

Doug observes that municipal governments are among the best-run in the country, with balanced budgets, excellent transparency, and good connections to the people that they represent and serve. Particularly concerning is the regular interventions by the provincial government in municipal affairs, creating worrying uncertainty about the direction we’re being taken. Doug mentions that this distraction caused by provincial interference has been ongoing for twenty years. He asks some questions…

- “What are we to expect from a one man show?” referring to the provincial facilitator that is to be appointed by the province as part of the Bill 39 process. He refers to work already done by the likes of Seiling and Fenn. An opinion piece by a person that does not live in the Region should be viewed with skepticism.

- "Do amalgamations save money?” As we seen in a few presentations already, and in Doug’s as well, is that this is not close to being a sure thing. In most cases it appears that it is very difficult to quantify any savings.

- “Are less politicians good for our political health?” While some would say yes, it’s been used as a way to . Less politicians means less access, and less ability of the remaining politicians to manage the challenges of a large municipality. This leads to bureacrats taking over responsibility that better belongs in the hands of accountable, elected leaders.

By many measures, Waterloo Region has been very successful with its current structure, leading one to wonder what the proposed benefit would be. Comparisons to the United States, London (UK), and Paris (France) show that unamalgamated cities with multiple tiers are common and successful. In the USA (San Francisco and Boston as examples that also have strong technology sectors), a dearth of amalgamations in the last century has led to many municipalities working well together in close proximity. Cooperation agreements are the normal way of working together rather than the consolidation of political structures. There are many global cities that have succeeded with reducing to a single-tier structure.

Doug challenges “Why would you want to amalgamate the Region of Waterloo?”, because based on many measures there is little room to improve on the performance of an already topnotch region.

Takeaways:

- Amalgamations don’t work, and don’t bring the promised benefits.

- Having multiple municipalities in Waterloo Region gives newcomers a meaningful choice about where to live.

- Any decision about amalgamation should be approved through a referendum.

Jim Erb

Jim is a Waterloo Region councillor and a former councillor for the City of Waterloo. Jim began by asking the audience to imagine the region from up in the air, and asking themselves if the seven municipalities make sense today. Based on his experience as a city and regional councillor, the municipal structures are getting in the way of effective governance. The current structure of cities and townships is an outdated and cumbersome model that gets in the way of good governance.

Jim is disappointed by politicians that show a shifting position on amalgamation during elections, and while in office. Additionally, the 66 municipal politicians are tripping over themselves and over the two-tier structure. He points to London and Hamilton with comparable populations having 16 councillors each. Toronto, a much larger municipality, has 26. This latter point was alluded to by the previous speaker in the context of provincial changes to municipal government. It’s not clear from the presentation how many of these are full-time politicians.

Likewise, municipal staff spends much of their time in collaboration and competition with their counterparts in other organizations. Coordination on matters such as the Official Plan, housing strategy, and response to the Pandemic was slowed by having 8 councils and staff involved. Duplication in fire service, legal support, and planning makes for inefficient service provision. Depending on the size of the lower-tier municipality, this leads to uneven service across the region. With many services already consolidated at the Regional level, Waterloo Region is closer to being a single-tier government than many others were twenty years ago (Ottawa, Hamilton, Toronto, etc). Having a single voice for economic development is necessary to act on the same level as local comparators.

Nonprofit organizations have led the way in merging or evolving into regional organizations, and Jim highlighted the Waterloo Region Community Foundation, YMCA, Community Connections, and Sustainable Waterloo Region as examples.

Finally, Jim disputed that amalgamation would lead to a loss of civic identity. Communities within the townships thrive as distinct communities within a larger municipality.

With his tongue planted firmly in his cheek Jim suggested that if an amalgamated city was for some reason not named Waterloo, that it could be named Erbsville.

Takeaways:

Jim is disappointed by politicians that show a shifting position on amalgamation during elections, and while in office. Additionally, the 66 municipal politicians are tripping over themselves and over the two-tier structure. He points to London and Hamilton with comparable populations having 16 councillors each. Toronto, a much larger municipality, has 26. This latter point was alluded to by the previous speaker in the context of provincial changes to municipal government. It’s not clear from the presentation how many of these are full-time politicians.

Likewise, municipal staff spends much of their time in collaboration and competition with their counterparts in other organizations. Coordination on matters such as the Official Plan, housing strategy, and response to the Pandemic was slowed by having 8 councils and staff involved. Duplication in fire service, legal support, and planning makes for inefficient service provision. Depending on the size of the lower-tier municipality, this leads to uneven service across the region. With many services already consolidated at the Regional level, Waterloo Region is closer to being a single-tier government than many others were twenty years ago (Ottawa, Hamilton, Toronto, etc). Having a single voice for economic development is necessary to act on the same level as local comparators.

Nonprofit organizations have led the way in merging or evolving into regional organizations, and Jim highlighted the Waterloo Region Community Foundation, YMCA, Community Connections, and Sustainable Waterloo Region as examples.

Finally, Jim disputed that amalgamation would lead to a loss of civic identity. Communities within the townships thrive as distinct communities within a larger municipality.

With his tongue planted firmly in his cheek Jim suggested that if an amalgamated city was for some reason not named Waterloo, that it could be named Erbsville.

Takeaways:

- Waterloo Region has more politicians for the population than any regional comparators

- Competition and complexity amongst municipalities create inefficient structures and convoluted experiences.

- Provincial and municipal leaders are the ones responsible for dragging their feet on reform.

Audience Voices

With six excellent speakers, there wasn’t much time remaining for discussion but the chat section was very active throughout the panel discussion. A few highlights of this discussion are below:

|

“Better two-tier models might be interesting to discuss more at some point as well, e.g. regional council be composed of all regional councillors to simplify the voting process, etc. Local councillors are who citizens like myself turn to about issues, but they often have little power over most things except for very minor concerns/issues, leaving citizens confused, feeling a lack of agency… I find myself and others I know are much more likely to talk to our councillor because of how locally rooted they are.

9000 per politician seems pretty good to me. I think the either/or of keeping very local representation and some kind of further amalgamation is a false question. I think we can be more creative in how we amalgamate our local political systems if we want to amalgamate our services.” - Andrew Reeves “We can make the residents' experience more seamless through collaboration among the municipalities, and find any relevant cost savings, without taking on the cost and workload of an amalgamation transformation.”

- Jason Hammond “Our social service sector is tired of dealing with 8 different governments and 60 political office holders to bring their services online. Our labyrinth of local governments is chasing away or hindering home building, investments, and social service delivery. Waterloo Region lost out on 1400 jobs – representing nearly as many families who rely on those jobs – because when Schneider’s Meats had to decide about where to grow its business, we couldn’t compete fast enough against Hamilton. Hamilton could go faster and be a better economic development partner because they are one single-tier city.”

- Rose Greensides “When looking for non-profit or business support, the option of dealing with one department/manager who is now dealing with a bigger portfolio scares me just as much as managing several relationships. I honestly don’t know what is better. The research showing it’s not actually more efficient to amalgamate makes me wary.”

- Alex Szaflarska “I worked at the CIty of Toronto before, during, and after amalgamation. After amalgamation very little got done in Toronto’s council Where before all councillors in the individual cities could agree on matters in their city, after amalgamation the councillors who weren’t representing an area of a former city would vote against items that would benefit that former city, no matter how beneficial. But that was multi-city to one-tier amalgamation, different from what we have in Waterloo Region. Small government is good government.”

- Bob Jonkman “One theme that comes up repeatedly is that different levels of government point fingers at each other. We are thinking amalgamation will solve this because the area municipalities can’t point fingers at the region and vice versa, but we will all continue to point fingers to and from the province. That part won’t change.” - Paul Nijjar

“Currently, we have made it clear that our rural townships will keep a rural focus and our local farms are thriving as the most profitable in Canada earning more per acre than others and being one of the largest components of our regional economy. Under amalgamation how do we protect these rural lands when rural Councillors are so easily outvoted by far more numerous urban Councillors? The pressures of growth, developers and development is intense and so far we have avoided the land speculation seen in most of the province because of the expectation set that our four townships will remain rural.”

- Kevin Thomason “66 politicians is not too many decision-makers but far too few. Communities at the neighbourhood level should be meeting in assemblies to decide how their communities are to function. Workplaces should be organized in the same way. Then we might be able to talk meaningfully about “democracy” - rule by the (common) people - including in its most important settings, where people work.” - Peter Eglin

|